Record labels come and go, of the thousands that started up in the post-war boom of indie labels, only a few survive today and many of them in name only. Some are revered by collectors for their unique sound, their contribution to the evolution of popular music, the hits they produced, how they adapted to changing taste and sometimes even, the business acumen of the owners. Most were successful in at least one of those areas but eventually failed, or were swallowed up by larger enterprises, because they lacked in another area, usually business acumen.

Atlantic Records, founded in New York City in 1947 was spectacularly successful in pretty well every area. It evolved from a shoestring operation working out of a seedy hotel room to a major corporation and even when it merged with an even larger corporation it never lost its identity; it continues today as a force in popular music.

The story of Atlantic’s beginning is well documented, but it’s the most interesting part. Its founding father was Ahmet Ertegun, the son of the wartime Turkish ambassador to the United States. Ertegun saw a lot of the world while he was growing up. He and his brother Nesuhi had developed a love of jazz while their father was stationed in London, England before the war so when the family moved to Washington, DC, they took full advantage of their newfound access to American culture; they went to all the jazz clubs and, because they could, often invited musicians to come to the embassy and jam. The Muslim brothers also put on shows at the Jewish Community Center, the only place in Washington that would allow a mixed audience. When their father died in 1944 the family moved back to Turkey but Ahmet and Nesuhi decided to remain in the United States.

Ahmet worked in a record store while attending Georgetown University and decided to get into the newly revitalized recording business to help pay for his studies. Despite his privileged background, Ertegun didn’t have the resources to start a record label on his own but he had developed a circle of friends with all the right talent, and enough money to pull it off.

Primarily there was Herb Abramson and his wife Miriam. Herb was a dentistry student and jazz fan; he had already founded a couple of labels that had moderate success. Miriam was very good at accounting and running an office. They got some more financial backing from the family dentist, Dr. Vahdi Sabit. As Ertegun put it later, all he wanted to do was sign artists and make records that he would like to buy.

They set up shop in any place they could find, renting spaces in various down-scale New York hotels. Herb Abramson was the president but his wife Miriam may have been the most important person in the organization. She was blunt and tough, often caustic. While the company was driven by passion for music, Miriam made sure they understood the bottom line. She was one of the first women executives in music, or any high-level business, a true pioneer, one of many pioneers at Atlantic.

In 1952 Ertegun hired a young engineer named Tom Dowd to handle the recording end of things. Dowd was a classically trained musician, proficient on a number of instruments and had been lead conductor of the Columbia University Band. He was also a brilliant mathematician and physicist. While serving in the U.S. Army he contributed to the development of the atomic bomb.

Dowd was assigned to work in literally a makeshift studio. By day it was an office, where they signed up talent. At night Dowd had to move the office furniture out and put together a studio to record that talent. Most of the recording equipment at the time was re-purposed radio station gear, Dowd hated it and immediately set about to improve it.

Dowd rebuilt everything using his skills to remove as much distortion and unwanted harmonics as possible. He was the first to use sliders instead of dials on the sound board. His changes had a ripple effect throughout the whole music industry; this little upstart company set the standard for sound quality. Under Dowd’s insistence, Atlantic was the first company to have an 8-track recorder, well ahead of Abbey Road Studios, which was the most advanced facility at the time. Dowd’s engineering made Atlantic’s records sound good technically but he was also passionate about music and found that, because he was a musician, other musicians were more open to his suggestions. He gradually became a producer rather than an engineer and played a big part in developing Atlantic’s unique musical identity.

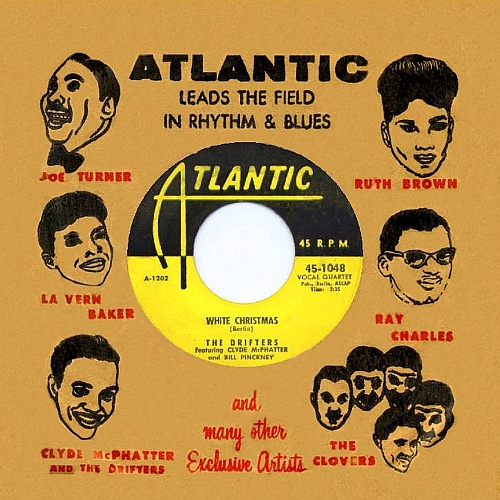

The first Atlantic recordings were mostly modern jazz and spoken word; they didn’t fare well in the market. Then in 1949 Ertegun got Brownie McGhee’s brother, Stick McGhee, to re-record a song he had done earlier for a label that had gone broke. Drinkin’ Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee, an upbeat, unsophisticated R&B number was Atlantic’s first hit. Ertegun signed more R&B acts that year, first Ruth Brown and then The Clovers, and one of his jazz idols, Joe Turner. He wrote songs for them under the pen name A. Nugetre (Ertegun spelled backwards) and encouraged them to try to put aside their musical training and pay attention to what youngsters wanted.

It was a difficult task; make music that was sophisticated and street-wise at the same time but Ertegun assembled a team of writers and producers, Jesse Stone and Jerry Wexler primary among them, who did just that. They knew their best material was being covered by white performers with far greater commercial success but they wanted to produce black music that would be accepted by both black and white listeners.

Their biggest discovery of course was Ray Charles who up to then had been a smooth jazz crooner but at Atlantic electrified the music world with his rootsy, gospel-tinged R&B sound. (In his autobiography Charles insisted his conversion was entirely his own idea, and it’s true, his recording of Hey Now, made before he joined Atlantic, is pure Ray Charles as we know him).

The team at Atlantic really found what they wanted when they leased Riot In Cell Block #9 by The Robins from a small Los Angeles label. The record was moderately successful and Ertegun loved the sound so much he bought the label and signed its owners, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, to an independent producer’s contract, the first in the industry. The Robins re-organized and renamed themselves The Coasters, Leiber and Stoller became the top producers in the business, churning out dozens of hits for the Coasters and the Drifters. Atlantic Records was now big in rhythm and blues, and rock ’n’ roll, the fastest growing genres in American music. Ahmet's brother, Neshui, ran the jazz division, with great success.

Everything was going great until 1959 when Ray Charles, their biggest star, left the company. It was a huge blow and the two music principals, Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler reacted in two different ways.

Wexler was committed to rhythm and blues, after all he had invented the term as a journalist. He pursued a deal with Stax Records in Memphis that made Atlantic (and Stax) a lot of money and undisputed kings of soul music. That relationship eventually went sour, as did his tenure at Atlantic but not before he produced records by Solomon Burke, Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding and his crowning achievement, Aretha Franklin.

Ertegun, having had success with Bobby Darin, decided the future was with white artists. He signed Sonny and Cher, the Young Rascals and British sensation, Dusty Springfield. Acting on Springfield’s recommendation, he signed Led Zeppelin and a few years later, (at Mick Jagger's insistence), The Rolling Stones.

By then the company that Wexler once described as “making … black music with black musicians for black adult buyers perpetrated by white Jewish and Turkish entrepreneurs” had become the number one record label in the U.S. Usually at this point the story goes on about the decline but although Atlantic is no longer independent, all the founders are gone and we oldsters don’t recognize the names of its artists, it never faded away. The company just changed with the times, something it was always good at doing.