There is nothing more delightful than watching a child dance and sing.

Almost every youngster does both naturally, it’s only later in life that we learn to hold back. Maybe that is why children’s songs are so appealing to us as adults; they take us back to that place.

Children’s songs, or nursery rhymes, are an important element in our popular music. If you look at a list of what are considered classic nursery rhymes, it’s hard to find one that isn’t at least part of a hit song.

The lines are really blurred; many children’s songs were written in medieval times for adults. It is thought they were social commentary, protest songs. Criticizing the government could get you killed so writers cloaked their messages in songs that were simple and bouncy. Those same qualities made them appealing to children and they eventually became children’s songs, their original meanings were lost in time.

Some well-known examples, such as London Bridge Is Falling Down and Ring Around the Rosie are said to have rather macabre origins. Ring Around the Rosie is often cited as being about the Black Plague while some say that London Bridge is actually about the medieval practice (and this really happened) of encasing live people in bridges in the belief that their spirits would keep the bridge up. Makes you yearn for the good old days.

All of this is speculative of course; most of these songs came from an oral culture so lyrics changed constantly. Nobody can say for sure what their origins are, but it makes for a fascinating study.

Iona and Peter Opie, a married English couple who began collecting and studying children’s songs in the early 1940s are the pre-eminent pioneers of the academic study of children’s culture. They were not the first, but the Opies dedicated their entire lives to researching, collecting and writing about children’s songs. They catalogued and categorized each one and tried, as best they could, to determine the origins. Their writing, research notes and vast collection of ephemera has all been digitized and made freely available to the public online so the Opies work is the primary source of information for any researcher.

They used many different categories; clapping songs, action songs, counting songs, story songs etc. but ultimately everything was divided between songs written for children and songs written by children.

Songs written for children were often sanitized versions of adult songs. Songs written by children usually were parodies of adult songs, sometimes with profane lyrics, the kind you don’t say with adults present.

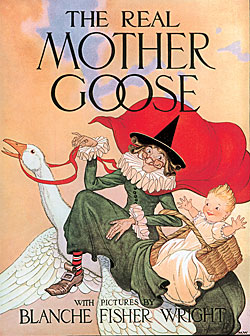

The first written anthologies of children’s verse, called Mother Goose Rhymes, started to appear in the 18th century. But just who was Mother Goose? Again, nobody really knows. There are two prominent theories (both dismissed by the Opies).

Americans will tell you the original Mother Goose was a Boston woman named either Elizabeth or Mary Goose who had a large brood of children and grandchildren that she constantly entertained with stories and rhymes in the late 1600s to early 1700s. However, the first written reference to Mother Goose, or mère l’Oye, appeared in France in 1695. Charles Perrault, who is credited with inventing the fairy tale genre, used it in the subtitle of his first book which suggests he assumed his readers were already familiar with the term.

This gives credence to the other contender, the wife of King Robert II of France who was known as “Bertha the Spinner” because of the tales she told and “Goose-foot Bertha” for unknown reasons. However, Bertha lived in the 10th century, we know she existed because of her royal heritage but we don’t know a lot about her daily life so it’s all speculation again.

Boston, and Massachusetts, can rightfully lay claim to one very popular children’s verse, Mary Had A Little Lamb. The verse, which later became a song, was written in 1830 by Boston resident Sarah Hale, in which she tells the story of a real person, Mary Sawyer of Sterling, Mass., who really did take her pet lamb to school one day, causing quite a commotion.

Besides being a staple in children’s literature, the verse was also the very first thing Thomas Edison recorded on his new invention, the phonograph. Edison probably didn’t realize this, but it was obvious that nursery rhymes were perfect fodder for the popular music industry that the phonograph helped foster. They were well-known, innocent, catchy and best of all, not protected by copyright. In the jazz age many popular songs borrowed lyrics from nursery rhymes, perhaps the most successful being Ella Fitzgerald’s recording of A-Tisket, A-Tasket in 1938. That song, which was based on an old children’s rhyming game, launched her very formidable career.

Still, children’s songs were considered just fun and games until the mid-1950s. The change started in 1947 when folk icon Woody Guthrie released an album of songs he had written to entertain his newborn son, Arlo. His Songs to Grow On for Mother and Child was the first “serious” children’s record. Soon after, another very well-known folk singer, Pete Seeger, released American Folk Songs for Children which established him as the grandfather of children’s music. A lesser known but still important musician, Ella Jenkins, released a music instruction album, Call and Response, in 1957 that included chants, melodies and rhythms from all over the world. All of them, it must be said, had a political agenda (Pete Seeger was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party) but these albums, and others, changed our perception of children’s music. They laid the groundwork for Sesame Street and the many full-time professional children’s entertainers we have today.

Nursery rhymes continued to be fodder for commercial songwriters, even more so with the birth of rock ‘n’ roll. Right from the start, with Rock Around The Clock (a counting song) rock ‘n’ roll was basically nursery rhymes for adolescents. Schoolyard skipping songs, rhythmic clapping songs, nonsense rhymes – they’re all in there. Their use became more subtle as rock ‘n’ roll progressed into more complex music, but it never went away.

One hit pop/kiddie song, Morningtown Ride, defines convention. It was an international hit for the Australian group, The Seekers in 1966 and was written in 1957 by Malvina Reynolds who also wrote Little Boxes, a protest song (she was decrying the sameness of suburban America) made to sound like a children’s song in the age-old tradition. However, with Morningtown Ride she wanted to create a new kind of lullaby. She noticed that children hate to go to bed at night because to them it was the end – it cut them off from everything. Morningtown Ride tells them that going to bed is the beginning of a journey to morning, one that they have control of.

Today in pop music there is a resurgence of borrowing from nursery rhymes. Rap and Hip-Hop are both rooted in Mother Goose. Taylor Swift, as part of her quest to make us believe she is an innocent muffin that has had fame thrust upon her, does it a lot.

I know it’s all part of a carefully constructed plan but my three-and-a-half-year-old granddaughter loves to dance to Taylor Swift songs and there is nothing more delightful than watching a child dance and sing.