Think of a technology that profoundly changed the way we interact with each other. You know the first one that allowed us to share music with almost anyone anywhere in the world and gave amateur musicians a chance to record their songs without having to be signed to a record label.

Oh it had a bad side; it allowed people to make illegal copies of material that was protected by copyright. Then again, it enabled political dissenters to spread their messages in repressive regimes and helped change the course of history, especially in the Middle East.

All this could be, and has been said of the digital revolution and the resulting social media but I’m referring here to an older, almost forgotten technology; the cassette tape.

Remember the Compact Cassette? Introduced in the 1963 it was at first derided for its low-quality sound but by the 1980s pre-recorded cassettes were actually out-selling vinyl LPs. Why? Because they were more convenient and portable, that’s why.

The Compact Cassette caused the biggest shakeup in the recording industry since Edison got it going and that’s only a small part of its cultural importance. Although it was pretty well killed off by the compact disc in the 1990s, the lowly cassette is now undergoing resurgence in popularity among some dedicated music fans. Collector Weekly magazine recently ran a very in-depth article on the subject and there are a couple of film documentaries about what is called “cassette culture”. That culture arose specifically because of the cassette’s humble origins.

The Compact Cassette caused the biggest shakeup in the recording industry since Edison got it going and that’s only a small part of its cultural importance. Although it was pretty well killed off by the compact disc in the 1990s, the lowly cassette is now undergoing resurgence in popularity among some dedicated music fans. Collector Weekly magazine recently ran a very in-depth article on the subject and there are a couple of film documentaries about what is called “cassette culture”. That culture arose specifically because of the cassette’s humble origins.

The Compact Cassette, a trademark name, was developed by the Philips Company in Belgium. It was more of a packaging innovation than a technical one, based on pre-existing magnetic tape technology which had been around for decades.

Magnetic tape had already revolutionized the recording studio in the 1950s. Up until then, recordings were still cut on a lathe, pretty much the same way Edison had done. Magnetic tape allowed for multi-track recording, overdubs and editing. Reel-to-reel tape recorders soon became standard in every studio. Home recorders were also available but they were bulky, expensive and a little bit too awkward for the average consumer.

Philips’ invention used much smaller tape running at half the speed of the slowest reel-to-reel and was initially designed for dictation only. They gradually improved the tape quality until a couple of years later it could do a passable job of recording music. Their brilliant stroke though was a business decision; instead of trying to make money from licensing fees, they gave the rights away for free. Their design became the universal standard; there was no incentive for anybody to create a competitive format. Now every consumer electronics company in the world could concentrate on making it sound better, which they did very successfully.

Once the cassette got to the level where it was as good as the 8-track tape (for all its drawbacks, it did have better fidelity) Compact Cassette players became standard equipment in cars and record companies started issuing their new releases in cassette form. Home cassette recorders were cheap, easy to use and relatively reliable. In the 1980s, the Sony Walkman pushed the cassette to the top of the heap. Recorded music was now portable, easy to copy (oops) and easy to make at home.

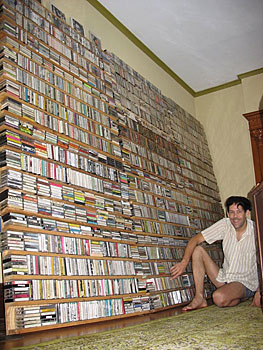

In the 1970s amateur musicians who had no hope of ever getting a recording contract started making and distributing their own cassette recordings. Anybody from the local church choir to the punk band thrashing around in a garage could make a recording and, with relatively little effort and cost, produce enough copies to get it out to their fans. The cassette case was durable enough that you could trust it to the mail, which gave rise to the cassette culture; a vast, world-wide network of indie music bands that trade cassette tapes by mail; you listen to mine, I’ll listen to yours. It became a thriving community that continues to this day, many of the bands insisting on using cassettes even though recordable CDs and downloadable music files would seem to be a better alternative. Many like the lower fidelity of the cassette, it sounds like a recording. Recordable CDs (CD-Rs) may sound clearer at first but they are unstable, many just don’t work from the get go, the rest will deteriorate after a few years. Downloading files is too impersonal for them. You can share hundreds of files on the Internet without ever listening to them and without having any interaction with the people with whom you are sharing. Where’s the fun in that?

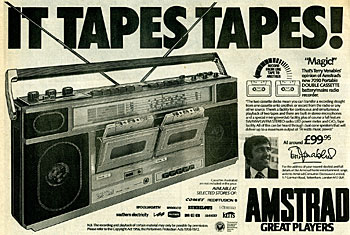

The cassette also enabled a different way of sharing music; actually listening to it, in groups, on the street. So-called boom boxes in the 1980s were large, loud and expensive devices that always incorporated at least one cassette drive. Now kids could not only listen to music outside, they could play it for their friends, or the whole block. It was the start of the hip-hop movement that still flourishes.

The cassette also enabled a different way of sharing music; actually listening to it, in groups, on the street. So-called boom boxes in the 1980s were large, loud and expensive devices that always incorporated at least one cassette drive. Now kids could not only listen to music outside, they could play it for their friends, or the whole block. It was the start of the hip-hop movement that still flourishes.

Of course there is the issue of sharing copyright material. At first some of the record companies embraced the idea, even putting out cassettes that had pre-recorded studio material on one side and were blank on the other, so you could make a copy of your favourite records to play in the car. No problem there but if you made two copies and gave one to a friend, problem. Record company executives are, well, executives, not artists. To most of them the idea of someone sharing their output for free was just too much. The companies embarked on a publicity campaign with the alarmist headline “Home taping is killing music”. It didn’t work; people continued to share and music didn’t die.

Cassettes helped spread more than music. They also had the unintended effect of allowing political and educational messages to be spread in remote areas and to people who could not read. In Iran in 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini used cassettes to spread his revolutionary ideology and overthrow the Shah. Soldiers could send recorded messages to their loved ones at home; journalists could record interviews and commentary almost anywhere. We take all this for granted now but it really was the Compact Cassette that democratized audio recording, and changed history.

By the late 1980s, with the CD and digital technology becoming cheaper and more accessible, pre-recorded music cassettes began to lose popularity. When CD-Rs became ubiquitous, millions of cassettes ended up in the dump. The format is still used for some voice recording (though cheap digital recorders are putting an end to that) and it is still popular in many developing countries because of its cheap cost. For most of us though, the cassette is a part of history, not something we would actually use.

The other problem is getting good cassette machines. In the early days there were many hi-quality recorders, players and dubbing machines. As the cassette faded, companies put less effort into the machines, most of the ones available now don’t hold up for long and the old ones, with a lot of plastic gears and rubber belts, are difficult to repair.

The music-trading cassette culture is keeping it alive for now. There are quite a few very small, niche record labels that still issue music on cassette and the culture is expanding with a lot of young people enthusiastically getting on board. Many of the old guard of traders view them with suspicion. They see the revival as a retro technology fetish, just a way to be hip in a digital world, and it won’t last.

If nothing else though, the cassette revival is highlighting how important this little plastic case was in our history and that it deserves more respect. So don’t throw out all your cassettes just yet, put at least one homemade tape in a place of honour.