It’s all about being in the right place at the right time and if you had aspirations to be in the music business in the late 1940s, Nashville was the right place. It wasn’t yet Music City; there was no music industry there like it is now, it was wide open.

We now think of Nashville as synonymous with country, but it also played a big part in the development of blues, R&B and gospel, the building blocks of rock ‘n’ roll. Memphis may have the reputation of bringing it all together with Elvis and Sun Records and popular myth has it that Allan Freed’s radio show in Cleveland turned white teenagers on to R&B but in fact, that happened in Nashville first.

It’s a story of record companies and radio. Both businesses had a target audience, but their products were available to everyone, sometimes with unintended results.

Records were big business by this time and distribution was key. It was easier in the north with its large cities and urban areas, but the south was still mostly rural; you couldn’t put stores within easy reach of most of the population, so mail order was the best option. The only trick was to get people to hear your product so they could order it.

Naturally, that meant radio play. Popular and big band music was easily heard on big national broadcasters but the local, folk music if you will, didn’t have an outlet that could be heard outside the rage of small, local stations.

Nashville, being a large centre, had bigger radio stations. The maximum power allowed was 50,000 watts and WSM in Nashville was one of the first to get to that level in 1932. They also had what is called a clear channel license meaning no other station in North America could use their spot on the dial, 650 AM. They famously broadcast what became the Grand Ole’ Opry in 1925. It played a big role in the development of the country music industry but another, lesser-known Nashville station played an equally if not more important role in popular music.

WLAC, at 1510 on the dial, also had a clear channel license though they couldn’t afford the 50, 000 watts until 1942 and the higher spot on the dial meant their signal would never be as clear as WSM’s. Owned by the Life and Casualty insurance company (hence the call letters) they broadcast the usual big band hits in the 1940s. With the success of WSM and country music they were driven to try something new.

Although it was a corporate owed station with an all-white staff they saw an opportunity in targeting an audience of southern blacks because there was no other major station in the south playing their music. In 1946 one of their DJs, Gene Nobles, started playing what were called “race” records, something unheard of for a white station at the time, especially in the south. The idea caught on with audiences and, more importantly, advertisers. By the early 1950s, WLAC was playing R&B, blues, and gospel exclusively during the nighttime hours.

The nighttime thing was important. The AM radio signal travels much farther at night so they could include the entire south, at least five or six states, in their target audience, making it ideal for mail order businesses.

We are now used to FM radio, where the stations are always local. The signal actually travels a very long distance but it’s in a straight line, so a station’s range is limited by the curve of the earth. It doesn’t matter how much power is used; the audience literally falls away with distance.

AM radio waves also have a limited range on the ground but part of the signal goes up to the sky. It bounces off the ionosphere then comes back to earth a bit farther away, getting around that curve problem. At night the ionosphere rises, the waves hit it at a greater angle and bounce much farther. This phenomenon combined with the clear channel license meant WLAC’s nighttime signal could be heard all over the eastern half of the continent, northern Mexico, the Caribbean and into Canada.

Their programming decision was also helped by the fact that most black owned stations could not afford high power and had the exact opposite of a clear channel license; their spots on the dial were so crowded they had to go off the air at sundown.

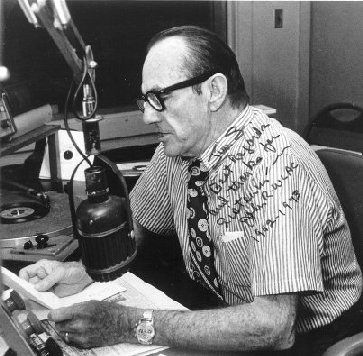

WLAC dubbed itself the “nighttime station for the nation” with shows hosted by Nobles and DJs Hugh Jarrett, John “R” Richbourg, Bill “Hoss” Allen and Herman Grizzard. These five white men, with their southern accents and folksy manners brilliantly managed the delicate trick of sounding black without sounding like they were trying to sound black. While WSM championed mainstream country, WLAC played the likes of Little Richard, Howlin’ Wolf, Etta James, and many other artists who, at the time, received almost no radio exposure.

WLAC dubbed itself the “nighttime station for the nation” with shows hosted by Nobles and DJs Hugh Jarrett, John “R” Richbourg, Bill “Hoss” Allen and Herman Grizzard. These five white men, with their southern accents and folksy manners brilliantly managed the delicate trick of sounding black without sounding like they were trying to sound black. While WSM championed mainstream country, WLAC played the likes of Little Richard, Howlin’ Wolf, Etta James, and many other artists who, at the time, received almost no radio exposure.

Besides the great music, the advertising was special. WLAC did it the old-fashioned way, instead of running a stream of 30 second commercials, they had blocks of time given over to a single sponsor, most of whom were mail order record shops. Because nighttime, out of market ratings were not measured, WLAC worked out a per inquiry model for charging advertisers, much like the per click model on Internet advertising. Every record played was offered for sale at the sponsoring store, usually part of a package of five records for around $3.

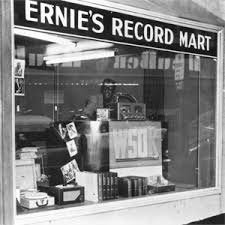

My favourite slot was sponsored by Ernie’s Record Shop, a store owned by genial Nashville entrepreneur Ernie Young. He got into the music business stocking jukeboxes, expanded into selling records, then making them.

He wasn’t a visionary with a plan; he just saw an unfulfilled demand and did his best to fulfill it. He originally opened his store to sell off his used jukebox records. When he saw that customers were looking for more gospel and R&B records than he could supply, he decided to make his own. He saw what Gene Nobles had done to make Randy’s Record shop a huge success and asked John Richbourg to do the same for him.

Young started Nashboro Records in 1952 for the gospel, market and then quickly followed with Excello for the secular R&B market. He had no idea how to make records; he set up a makeshift studio in the back of his shipping department and winged it. The acoustics were terrible, the studio piano was painfully out of tune and the artists were usually under-rehearsed. There were virtually no production values, sometimes even false starts made it to the record but with his built-in mail order distribution and his promotions on WLAC he almost couldn’t lose. He’d sign just about anybody but got a lot of established artists when other labels folded. Through it all he managed to make some great records that are favourites with collectors today.

Young started Nashboro Records in 1952 for the gospel, market and then quickly followed with Excello for the secular R&B market. He had no idea how to make records; he set up a makeshift studio in the back of his shipping department and winged it. The acoustics were terrible, the studio piano was painfully out of tune and the artists were usually under-rehearsed. There were virtually no production values, sometimes even false starts made it to the record but with his built-in mail order distribution and his promotions on WLAC he almost couldn’t lose. He’d sign just about anybody but got a lot of established artists when other labels folded. Through it all he managed to make some great records that are favourites with collectors today.

WLAC sold lots of other stuff such as baby chicks – get a hundred for $1.98 plus COD – Royal Crown hair dressing, razor blades, bibles, autographed pictures of Jesus, just about anything. The advertising was part of the patter; some of the DJs drank heavily while on the air so it got pretty colourful. Hugh Jarrett attracted the ire of the FCC in 1963, and lost his job, for suggesting that lovers should keep a 55 gallon drum of White Rose Petroleum Jelly in the back seat of their cars because “it helps things go in and out”.

WLAC made record store owners into millionaires and played a big role in making Nashville into a music centre but it also had huge effect on our popular culture.

Although their programming and advertising was aimed at southern blacks, white teenagers were listening in too. A whole generation of blues-based rock musicians including Duane Allman, Johnny Winter and Charlie Daniels credit WLAC as their first inspiration. Most suburban white kids of my generation, who would normally never get to hear black music, got their music education listening to WLAC. Many argue that popular music as we now know it would not exist without the barrier-breaking influence of WLAC.

The station is still on the air but it’s an all-talk outlet for Fox News. We’ll never see anything like it again, thanks to WLAC back in 1960s you didn’t have to be in the right place to hear great music, with some careful dial twisting, you could get it almost anywhere.